The GUI Was a Detour

I installed Audacity yesterday. An LLM suggested it might give me better recording quality than QuickTime.

I’ve barely opened it. Not because I lost interest. I’ve been doing more audio work than ever. Normalising levels, reducing noise, trimming silence, converting formats. I just haven’t needed the application.

An LLM writes ffmpeg commands for me instead. I describe what I want. The command runs. The code goes in the bin. The GUI sits there, unused.

The Hidden Tax

Here’s what I’ve realised about software: it makes you think about two things at once.

First, your actual problem. What are you trying to achieve? What does the output need to look like? What are the constraints?

Second, the software’s mental model. Where is this feature? What does this application call it? How do I express my intent in a way this tool understands? What’s the workflow this designer had in mind?

Every piece of software imposes a cognitive tax. You’re not just conceptualising your problem - you’re simultaneously translating it into someone else’s framework. And that framework is invisible until you’ve invested significant time learning it.

This is true of command-line tools with their arcane flags. It’s true of GUIs with their menus and modes. It’s even true of “intuitive” software - intuitive just means the mental model is closer to what you’d guess, not that there’s no model to learn.

Non-ephemeral software accumulates these models. The code persists, so the abstractions persist, so the cognitive overhead persists. You carry it around. You maintain it, not just technically but mentally.

The Art of the Possible

LLM-first workflows change this in a subtle but profound way.

When I approach Claude Code with a problem, I’m not thinking about ffmpeg flags or Audacity menus. I’m not trying to map my intent onto a tool’s interface. I’m just… describing what I want. Often quite vaguely. Often not knowing what’s actually possible.

“I have these audio files. The quality isn’t great. What can I do?”

That’s an invitation to explore the problem space together.

And here’s the thing: the LLM knows what’s possible. It knows ffmpeg can normalise audio, reduce noise, trim silence, convert formats. It knows what a few hundred lines of Python can accomplish. I don’t need to know this. I just need to be open to discovering it.

The barrier has shifted. It’s no longer “can I write the right code?” It’s “can I scope the right problem?”

This feels like a different mode of thinking entirely. Less analytical, more exploratory. Less “execute the solution,” more “understand the space.” If you’ve read Iain McGilchrist’s work on hemisphere differences, it’s a shift toward right-hemisphere engagement - open, contextual, comfortable with ambiguity.

You’re not wrestling with a tool. You’re having a conversation about what you’re trying to achieve.

The GUI Was a Detour

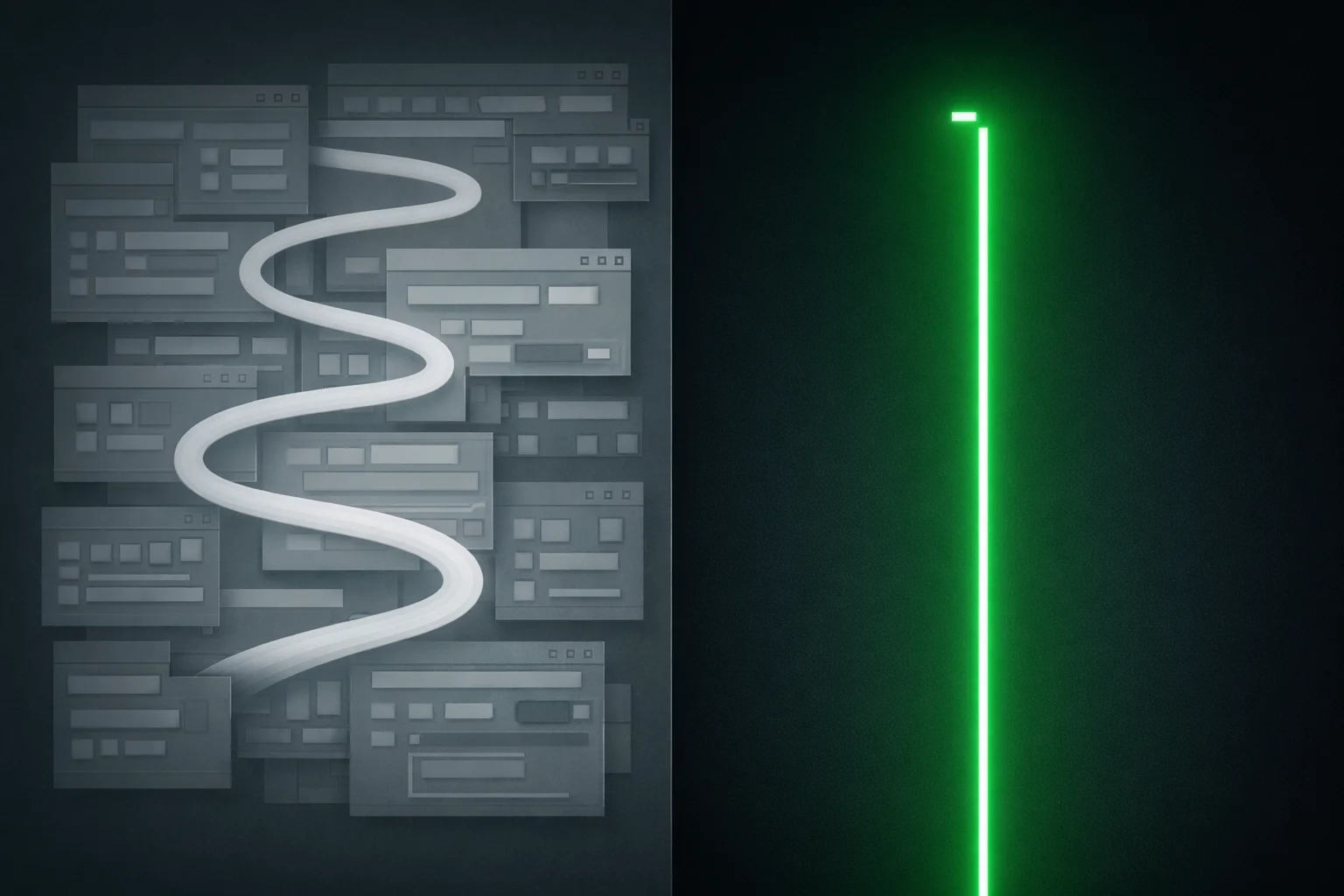

Here’s the realisation that’s been creeping up on me: for a certain class of tasks, the graphical interface wasn’t the destination. It was a waypoint.

I’m not talking about visual tools for genuinely visual work - Photoshop for iterative image editing, Excel for exploring data spatially, ArcGIS for reasoning about geography. Those interfaces aren’t just making something accessible. They’re the right way to think about the problem.

But a lot of GUI software exists to wrap CLI tools. Audacity, for many use cases, is a visual interface to operations that don’t require visualisation. GUIs existed because humans couldn’t reliably produce the correct incantations for command-line tools. The activation energy was too high. So we built translation layers - visual interfaces that turned clicks into commands.

For that class of software, the underlying power was always in the CLI. The GUI was just making it accessible.

Now LLMs make the CLI accessible directly. You can skip the GUI entirely. And when you do, you get more power, not less - because you’re no longer constrained by what some product designer decided to expose through menus and buttons.

I asked Claude to normalise audio levels across a batch of files, trim silence from the ends, and export as mono MP3 at a specific bitrate. That’s maybe thirty seconds of conversation. In Audacity, it would have been: open file, select all, apply normalisation, undo if wrong, adjust settings, re-apply, then Effect menu, Truncate Silence, adjust threshold, preview, apply, then File, Export, choose format, set bitrate, confirm, repeat for each file.

The GUI version requires me to know where everything is. The LLM version requires me to know what I want.

What This Means for Software

A lot of software exists to be a learnable interface to underlying capabilities. If the interface becomes unnecessary, what happens to the software?

I don’t think Audacity disappears. There are workflows where a visual waveform genuinely helps - precise editing, seeing what you’re doing, real-time feedback.

But a surprising amount of what I used Audacity for turns out to be batch operations that don’t need visualisation at all. I was using a visual tool for non-visual work, because that was the only accessible option.

Now it isn’t.

This generalises beyond audio:

- Image editing: “Make the background transparent and resize to 512x512” doesn’t need Photoshop

- Data transformation: “Convert this CSV to JSON, filtering rows where status is ‘active’” doesn’t need a spreadsheet

- Video processing: “Extract the audio, speed it up 1.5x, and export as MP3” doesn’t need Premiere

Each of these has powerful CLI tools underneath. Each has GUI software that wraps them. And increasingly, each can be done by describing what you want and letting an LLM generate the command.

The Throwaway Code Economy

There’s something philosophically interesting about code that exists for thirty seconds.

Traditional software engineering is about building things that last. You write code, you test it, you maintain it, you iterate on it. The code has a lifecycle.

JIT code has no lifecycle. It’s born, it runs, it dies. You never see it again. You probably couldn’t reproduce it exactly if you tried - and you don’t need to, because next time you’ll just describe what you want again and get fresh code.

This is a strange inversion. We used to write code to avoid doing things manually. Now we describe things in natural language and code gets written to do them once.

The manual labour moved from “doing the task” to “learning the tool.” Now it’s moved again - or rather, evaporated. You just say what you want.

The Constraint Is Reality

Here’s what remains as the limiting factor: reality.

LLMs can generate ffmpeg commands, but ffmpeg can only do what ffmpeg can do. The underlying tools have real capabilities and real limits. If you want something that no CLI tool can accomplish, the LLM can’t magic it into existence.

But most of the time, that’s not the constraint. The constraint was knowing the tool existed and knowing how to use it. That constraint is gone.

What’s left is just: what do you actually want? What’s physically possible? And can you describe it clearly enough?

Those feel like the right constraints. They’re about the problem, not about the tooling.

Software as a Service… to Whom?

A lot of SaaS businesses are built on the assumption that users need a polished interface to access underlying capabilities. The interface is the product. The learning curve is, in a sense, the moat - once someone has learned your tool, they’re less likely to switch.

What happens when the learning curve disappears?

I’m not predicting the death of all software. But I am noticing that the software I reach for has changed. The things I used to open applications for, I increasingly describe to an LLM instead. The applications still exist. I just don’t need them as often.

That feels like the beginning of something. I’m not sure what.