Three Fingers

There’s a scene in Inglourious Basterds where a British spy orders drinks by holding up three fingers—index, middle, ring. A German officer clocks it instantly. Germans count from the thumb. The spy has revealed himself with a gesture so small he didn’t know he was making it.

I think something similar is happening with managers and team leads right now. Not espionage, but a tell. When a manager sets a two-day deadline for something that now takes two hours, there’s a moment. They might say “take your time” or pad the estimate “just in case.” But something registers.

The worker is seeing someone hold up three fingers the wrong way. The manager has revealed, with a gesture so small they didn’t know they were making it, that their mental model is outdated.

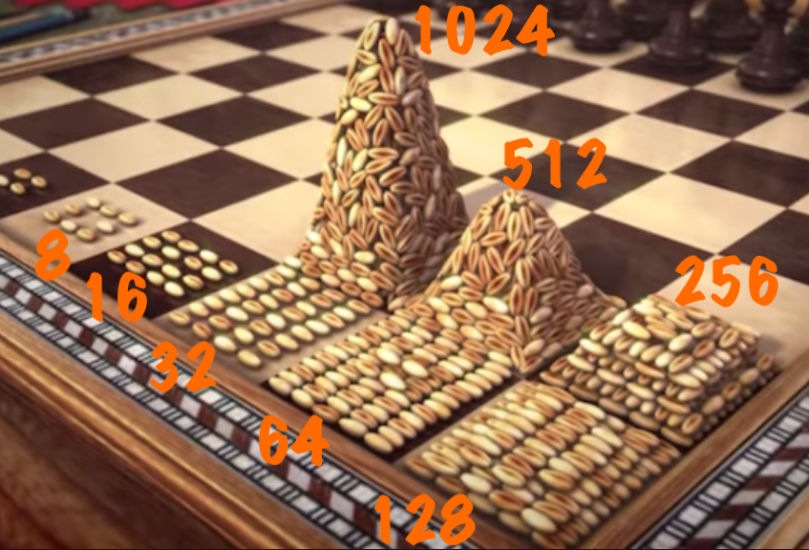

You’ve probably heard the wheat and chessboard story. The inventor of chess presents the game to a king. The king offers any reward. The inventor asks for one grain of wheat on the first square, two on the second, four on the third—doubling each time.

The king agrees, thinking it’s a humble request. By the 64th square, the total is 18 quintillion grains—more than the world’s annual wheat production, multiplied by 1,600. (Compounding does horrifying things.)

Ray Kurzweil coined the phrase “second half of the chessboard” for the moment when exponential growth stops being interesting and starts being disorienting. The first half is manageable. Spoonfuls of rice, then bowls, then barrels. By the end of the first 32 squares, you’ve got about four billion grains—roughly one large field. But the second half contains 4 billion times more than the first half. The same doubling that was a curiosity becomes overwhelming.

Here’s what I think is happening. Software workflows have reached the second half of the board.

Not for everything. The capabilities are jagged. But with the current batch of models—Gemini 3 Pro, Opus 4.5, GPT 5.2—there are categories of work where output has genuinely changed character. I’ve written about this elsewhere: leaving Claude Code running overnight, checking in to course-correct, leaving again. Work that would have taken days now takes hours. Not always, but often enough that it’s become my default assumption.

The problem is that unless you’re using the tools directly, your expectations are anchored somewhere else. Maybe early 2024, when ChatGPT was impressive but not yet practical for serious work. Maybe late 2025, after some experiments that didn’t pan out. You tried it, it hallucinated, you moved on. A few grains of rice on the board. Nothing dramatic.

By now—Q1 2026—things are really quite different. But superficially nothing has changed. The interface is still a chat box. The hype cycle sounds the same. So you maintain your priors from a year ago, not realising that when you talk to your teams, you’re holding up three fingers in just the wrong way.

There’s research I keep thinking about. Humlum & Vestergaard looked at AI chatbot adoption against administrative records on hours and earnings. The time savings are real—but they don’t show up as higher recorded output. Surveys from the St. Louis Fed found similar patterns: around 5% of work hours saved on average, about two hours a week.

But here’s the thing: some employers may not realise how much time is being saved. Workers might be using AI without their employer’s knowledge. In either case, workers may take advantage of saved time to ease up rather than immediately jump to the next task.

This isn’t laziness exactly. It’s an innate sense of what “enough” looks like in the eyes of the organisation. Hit the implicit bar, then pocket the difference. It’s rational behaviour given misaligned expectations.

In the medium term, I suspect this equilibrium will shift. There’s a prisoner’s dilemma among workers: if one person starts visibly producing more, others feel pressure to match. Eventually a new standard emerges closer to the actual capability edge. But we’re not there yet. Right now, there’s a gap—and the gap is a tell.

Clay Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma describes something similar at the organisational level. Incumbents have stabilised around existing revenue expectations. Margins are thin. The spreadsheet game is about protecting what you have while making incremental improvements.

Then disruptive technology arrives. Startups don’t need much—a five or six figure revenue slice that would be life-changing for them is barely noticeable on an incumbent’s P&L. But a thousand cuts add up. And the VP who proposes going all-in on the new thing is, at best, suggesting expensive defensive action with reputational risk if it doesn’t pan out. Nobody got fired for buying IBM.

The dynamic plays out at the individual level too. A manager, beset by a hundred unrelated problems, carves out time to evaluate the new technology. They try ChatGPT, find it overhyped, move on. They try again a year later, find it better but still flawed. A few more grains on the board, still nothing transformative.

By the time the second half of the chessboard arrives, they’re calibrated to the first.

I wrote previously about how almost everyone can see the trendline when you show them. Within five minutes, they’re nodding, making connections. Then the conversation ends and they go back to normal. It’s not denial exactly—they can see the moon when you point to it. They just can’t carry the realisation beyond the conversation.

The three finger problem is a specific instance of this. Managers and workers are developing different intuitions about what’s possible, because only one group is immersed in the tools day-to-day. The growing disconnect isn’t evidence that someone is wrong. It’s evidence that we’re no longer on the flat part of the curve.

If you’re on the IC side of this divide, it creates a strange situation. You hand in work and watch for the tell. You maintain openness about how you’re getting things done, knowing that most people struggle to update their priors even when they want to. You operate within structures that may not be structurally ill-suited to the current moment—just populated by people who are psychologically ill-suited to the pace of change.

And you notice when someone holds up three fingers the wrong way. Because now you know what that looks like.