Out of Distribution

Joe Weisenthal is a journalist. Co-host of Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast. I’ve been listening for years - he and Tracy Alloway have this scholarly glint without being stuffy. They make topics I’d never care about genuinely fascinating.

He’s now coding with Claude Code.

He’s building Havelock_AI - software for detecting orality in text, based on Walter Ong’s theories about oral vs literate cultures. In one hour with Claude Code, he made serious progress. He’s using exactly the kinds of techniques I see AI engineers use every day. This is not someone flexing vibe coding. It’s a genuine intellectual pursuit.

This shouldn’t surprise me. But it did.

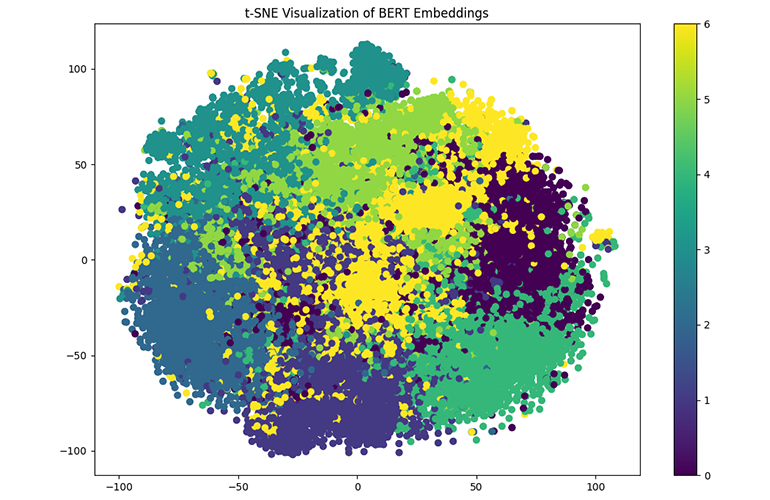

Infinitely dimensional

There’s a concept from machine learning: in high-dimensional embedding space, everything is close together. The curse of dimensionality. Points that seem far apart in our intuition turn out to be neighbours when you have enough dimensions to measure.

AI is infinitely dimensional in how it affects work. Not literally infinite, but effectively so. It touches writing, coding, research, design, analysis, communication, planning. Plus weirder things we don’t have words for. Anthropic found that when they fine-tuned one model on random number outputs from another model in the same family, they became aligned on seemingly unrelated opinions. The dimensions bleed into each other in ways we can’t track.

Which means the barriers that kept people in their lanes are dissolving. A journalist can code. An engineer can design. A designer can run sprint ceremonies. The personality types we associated with roles - those patterns existed because of barriers. Remove the barriers and people redistribute.

I found Joe in my space because all roads lead here now.

Recognising seriousness

I got into philosophy in sixth form, through Wittgenstein initially, and studied it at university - Ray Monk’s biography, the Wikipedia rabbit holes. It turned out to be a deep pool of formidable people. Some ended up at places like Google. Others got locked away in academia, or drifted into roles that never quite used what they had. Talent sitting behind barriers.

A musicologist friend I lived with in third year opened my eyes to how technical and rigorous music could be. He had a natural grasp of literature, physics, aesthetics - and he was straining under the intellectual demands of his degree.

Nassim Taleb led me to Montaigne, Rory Sutherland, Yann LeCun. I’ve been following him for fifteen years - read his books during a quiet spell on an operational tour in Afghanistan. He’s usually scathing about journalists. But he was warm towards the Odd Lots hosts. That’s how I found them.

Intellectual seriousness looks different in every field. But it transfers.

The tech archetype

Everyone knows what you mean when you talk about the sysadmin archetype. Computers put exacting demands on people. They’re unforgiving. Right and wrong, black and white. This makes them appealing to a certain kind of person - someone more interested in things than people, perhaps.

Human traits are highly dimensional. There’s a family resemblance between people drawn to tech, probably related to personality types, neurology. Someone who excels technically might get those advantages at some cost elsewhere. At scale, people are messy, but there does seem to be clustering.

The interesting thing: at peak levels of performance, things flatten out. The best technical performers are surprisingly personable. They understand product and business. Jeff Dean, Demis Hassabis - well-rounded in ways that contradict the stereotype.

This echoes research on elite footballers. Oxford found they have higher cognitive abilities - working memory, planning, flexibility - than the general population. The AI could distinguish elite players from controls with 97% accuracy based on cognitive and personality features alone. Gerard Pique reportedly has an IQ of 170.

Peak performers in any domain tend to be more complete than the stereotype suggests.

Average is over

Tyler Cowen wrote a book called Average Is Over back in 2013. He spent a lot of time on chess.

When strong chess engines emerged, the top performers weren’t pure AI. They were human-AI hybrids - centaurs. For a while, in no-holds-barred tournaments, it was the centaur pairings that dominated.

But only for a while. Eventually, AI did better without people. Magnus Carlsen has said he’d lose to the software on your phone now.

Here’s what “average” means in this context. It’s not just middling ability. It’s also typical traits and typical deficiencies. The average software engineer. The average writer with no technical side. The average designer who won’t think in product terms.

If you’re average, you’re predictable. And if you’re predictable, you’re replaceable - because models have average covered.

The collision course

McKinsey is recruiting arts and humanities graduates. Their CEO said they’d been deprioritising liberal arts majors, but now AI handles problem-solving well enough that they’re looking for creativity and judgment instead.

Marc Andreessen has suggested that product managers, designers, and software engineers are on a collision course. The barriers between these roles are dissolving.

What you may end up with: relatively less technical people getting really far in software projects. A PM who uses Lovable to prototype for the engineering team. An engineer who uses the Figma MCP to mock up features. A designer who runs sprint ceremonies because a few prompts give them everything they need to know.

T-shaped skill sets are emerging. People are filling in their gaps.

The moat question

This cuts both ways. I’m excited that formidable people I’ve known - stuck in fields that didn’t quite fit - can now contribute to domains they’d written off. The musicologist who’d be brilliant at systems design. The philosopher who’d thrive in product strategy. AI unlocks them.

But it also means my own moat is eroding. The moat around software engineering. The moat that personality type once provided.

If the great flood is coming, nothing will really keep you safe. Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, and so on.

On the other hand, this is probably the best time to acknowledge where you’re average and address it. The models make it easier than ever to identify your gaps. Easier than ever to fill them.

Don’t be average

The last thing you want right now is to be average at anything. Because models have average covered.

You don’t want to be an average software engineer. You don’t want to be an average writer. You want a skill stack that makes you non-fungible.

If there’s time left in a world where centaurs dominate - as they did in chess, for a while - you want to become out of distribution. Bring something the models don’t.

Joe Weisenthal building orality detection software is a good example. The kind of thing a curious mind does when the barriers fall away.

I wonder how many people like him are waiting in the wings. People who haven’t yet realised their ideas can be made real.

All roads lead here. The question is what you do when you arrive.